Mapping the Mythical

is a longtime project that aims at mapping the prime locations in Greece as seen, imagined, and visualized by Western painters in Europe.

The Mirror Image

Portraits form a triangle between the artist, the model, and the viewer. Each one of them projects an aura and understanding onto the image.

We all have in common age and the dilemma of getting older. Dorian Gray tried to escape this fact of life by exchanging his soul for his every youthful self-portrait but we are inevitably confronted with ourselves when looking into the mirror or seeing ourselves reflected.

How do we look at the image of another person? Does s/he get changed by the gaze of the viewer, by the eyes that stare at it? Or do we as viewers get changed? Does it change our perpection about ourselves as individuals? Do we enter the emotional and intellectual realm of the sitter? Can we take their place?

A show around mirrors, reflections, gazes becomes a game of changing identities, from the artist to the collector to the viewer to the portrayed, from thought processes to physical challenges, from portraits to scribblings to personifications, from the artist’s friends, to character, to celebrities.

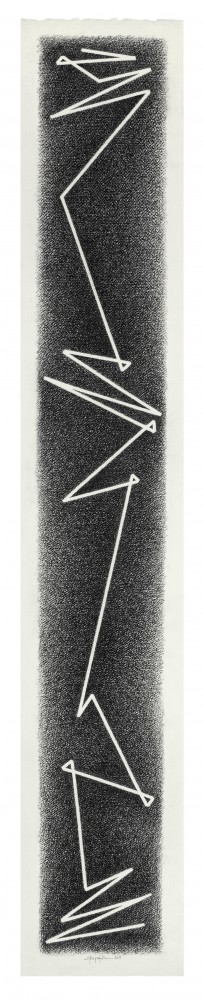

Not A Day Without Its Line

was a curatorial conceived in 2007 and presented to the Museum of Cycladic Art (but was never realized). Apart from underlining the importance of drawing as a basic skill in art, the concept interprets the line in a variety of roles.

The title is a quote translated from Pliny’s ‘nulla dies sine linea’, commenting on Apelles who said he never passed a day without doing at least one line, and to this steady industry owed his great success. Apelles is said to have gone to Rhodes to visit Protogenes, his rival and fellow painter. Not finding Protogenes in his studio, Apelles drew a line on a blank canvas to show off his ability. Upon entering, Protogenes picked up the challenge and drew a second line above the first one. Apelles picked up the brush again and drew a third one, fine and even, right in the middle. Protogenes claimed defeat.

The idea of a painting or drawing depicting three single lines at a time where hyper-realistic representations, were admired, is an interesting one and leads directly to our own experience with minimalism.

The show does not treat the line as ‘theme’ or subject but starts from the prediction that the line is a structural and basic element of many artworks, including drawing, painting, sculptures, as is the grid, or the dot. It wants to forward the proposition that one single line is not necessarily simple and as such is beyond the statement ‘I can do that’. It makes a link to minimal and conceptual art, two very influential movements that only slowly and difficultly found acceptance from the public at large because of their often austere theoretical or ideological premises. One important aspect therefore is to point out that basic structures are integral parts through history but that it is the perception that changes. A good example is the book by Quatremère de Quincy, ‘Mémoire sur le défi d’Apelles et de Protogènes’, essay, Universität Jena, 1868 – kept at the Gennadius Library -, written and published in the 19th century, where the writer interprets Apelles’ story completely within his own world and experience, unable to accept a literal version of the events and description of the work in question.

(Quatremère de Quincy cannot accept the idea that the painting conceived by Apelles and Protogenes would simply have consisted of three plain lines. He makes the case for more representational superimposing images that fit within the perception of ancient Greece as seen through the eyes of 19th century academicians. He talks about un ‘trait’ géométrique as an outline without shading, without colouring. It would take artists until the Quattrocento before they mastered perspective and were able to create an illusion of depth. Therefore, before that time, all representation was necessarily flat (two-dimensional) and the outline played an important role.)

In a similar sense, even if the imagined drawing by Apelles and a drawing by Donald Judd might show the same formal attributes, a drawing of three lines in Apelles’ time would have been completely unacceptable as an independent work of art and a source of ridicule, just as it remains inconceivable in as far as the 19th Century.

The show follows a number of concepts as incorporated in the works on displays, roughly:

The line within a Minimalist aesthetic

The line as element within Philosophy, Mysticism

The line as part of Geometry

The line as a architectural component

The line as spatial element

The line as pure outline

The line as means of Communication

The line as border

The line is a basic geometrical figure, used in primitive and ancient societies and cultures to convey messages, from the spiral, to the triangle, the labyrinth, or the meander (symbols). As such it becomes a means of communication that evolves into language. It was Aristotle who said ‘There can be no words without images’. The line was further used by artists as a way of dividing space and therefore guiding the viewer’s perception on a bi-, three, and even four-dimensional level. The line is a structural element crucial to modernist ideas and ideals about architecture and urbanism, from the city grids made up of crossing streets to the austerity and rationalism of high rise buildings.

Cogito, Ergo Sum

is a visionary display of works that represents a visual resume